"I am not the least afraid to die”

― Charles Darwin

― Charles Darwin

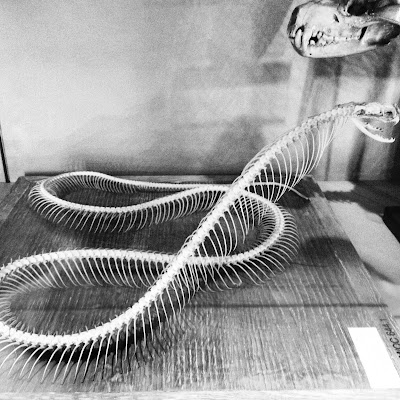

Look away now if you are of a delicate disposition, this place is not for the faint hearted. The Hunterian Museum is tucked away in the Royal College of Surgeons in central London. It houses an impressive collection of human anatomy, pathology, natural history and even art history which has been collected over the last 250 years.

It has the feeling of a private museum; off the beaten track, contained within a university. This may be deliberate as the exhibits require a certain degree of respect and dignity. In the late 19th century and early 20th the college was a major research hub for human evolution. Objects within the collection have generously informed the medical world and would've undoubtedly contributed to research which has found treatments and cures for many illnesses and medical conditions.

If anything, the museum is a celebration of the beautiful and most complex of all living creatures to exist on this earth: the human being. Tracing the very early and sometimes barbaric practices of dissection in the 16th century, the specimens move through the age of science and reason to modern day medicine.

| ||

| William Hogarth The Four Stages of Cruelty: The Reward of Cruelty 1 February 1751 Etching and engraving |

This etching by 18th Century artist, Hogarth is the final print of a series entitled 'The Four Stages of Cruelty'. It was a propaganda stunt to de-romanticise criminal life and act as a deterrent. But he may have gone too far; illustrating the noose still attached to the freshly hung victim's neck and the bones of another being boiled for later study. The skeletons of dissected criminals were usually refused a Christian

burial and subsequently displayed as specimens, as can be seen in the

niches to the left and right. Originally a surgeon did not study like a physician; instead they carried out apprenticeships and attended public dissections. However, it did seem that at the time there were simply not enough executions to meet the demand for public dissection. 'Body snatching' was a common practice; some criminals going so far as to murder people to sell their bodies to science. Can you imagine this type of thing going on in the UK today?

|

| The skeleton of the 'Irish Giant', Charles Byrne who stood at 7ft 7" |

I found the story of Charles Byrne quite moving. His exaggeratedly elongated skeleton peers over you from a glass case. Born in Co.Tyrone in the north of Ireland in 1763, Byrne soon became known as 'The Irish Giant', and eventually toured with a traveling show in England where people would pay to come face to face with this 7ft 7" (2.31m) titanic figure. It was later discovered that he suffered from the then unknown condition Giantism, which is when a tumor develops in the pituitary gland causing an overproduction of the growth hormone. This meant that his bones kept growing past adolescence and into adulthood. Though Byrne did not live very long, dying at the young age of 22, he was all too aware of vulturous demand for his corpse amongst the medical world and his dying wish was to be buried at sea.

However, sadly his body was sold to John Hunter, a wealthy and prestigious surgeon and collector of medical curios for the sum of £500. One journal allegedly said that on his death,

"The whole tribe of surgeons put in a claim for the poor departed Irishman and surrounded his house just as harpooners would an enormous whale."

But what did humans do before science? How have we managed to survive and multiply when so much has been against us? I found myself quite moved by the whole museum experience in ways that I had not anticipated. There is a part of me, as in all humans that is morbidly fascinated by such things. I don't believe that it is a type voyeurism, but rather a fear of death and a search for answers to our questions of immorality. This is not only relevant to our own fatality but that of our loved ones. You find yourself being slightly disturbed by what you're seeing and yet you can't look away. Personally, I wouldn't fancy some of my body parts petrified in a glass jar, bleached by formaldehyde and on public display. But then again, medicine wouldn't be where it is today if it were not for the collection and study of these specimens.

| |||||

| Skull and photograph of a Tasmanian Tiger, now extinct. |

There is a small section of the museum which houses specimens of species that are under threat or now extinct. Some were collected over 100 years before and include that of a Dodo, Panda Bear, Polar Bear and Mountain Gorilla. There is also the skull of a Tasmanian tiger. After the colonization of mainland Australia these animals became unique only to it's offshore state, Tasmania. They were called 'tigers' because of the stripes across their backs, however the Thylacine was actually the largest of the carnivorous marsupials. The very last one (pictured above in the photograph behind the skull) sadly died in captivity in 1936, after a barbaric 200 year campaign to demonize the unfortunate creatures and trophy-hunt them to extinction.

After two hours of being faced with cross sections of great anatomical detail: from a series of foetus showing the stages of gestation, which were both fascinating and upsetting, to diseased petrified and peni in glass specimen jars, my stomach had just about had enough. I was feeling a little peckish before I'd come to the museum, but by 4pm I had lost my appetite completely and swore never to touch a piece of meat again.

The place is a fascinating Aladdin's cave of pathology and natural science and should satisfy anyone's morbid curiosity and teach you to take better care of yourself.

The place is a fascinating Aladdin's cave of pathology and natural science and should satisfy anyone's morbid curiosity and teach you to take better care of yourself.